Close window | View original article

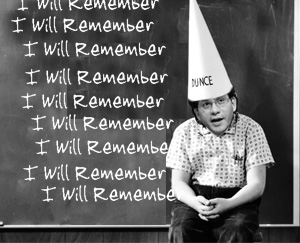

Bankster's Holiday 3 - Donning the Dunce Cap

The very worst crooks? The regulators!

The first two articles in this series explained how government meddling and incompetent, politically-motivated regulation grew the housing bubble, popped it, plunged our economy into a tailspin, and created a major fiasco as the banks hastened to clean up all the dud mortgages the government had encouraged the banks to write. This article explores some of the lessons to be learned from this mess.

The lessons won't do politicians or agency bureaucrats any good, of course. The political system encourages agencies to make any and all problems worse so they can ask for a bigger budget each year. This is OK with our lawmakers provided that they get campaign contributions as Fannie and Freddie gave so much to Rep. Barney Frank and Sens. Dodd and Obama.

The lessons are for the voters. After all, we are the only force which can keep the system under control. Unless we vote the rascals out, they'll keep stealing our money in return for campaign contributions as they have for the past 20 years.

Disaster Comes Slowly

The first lesson is that government-induced disaster comes slowly. Our economy is so big that it takes time for all the bad effects to become obvious, by which time it's usually too late.

Fannie Mae was set up in 1938 during the Great Depression to try to put some life in the housing market. It was converted into a stockholder-owned corporation chartered by Congress in 1968.

Being a creature of Congress but having stockholders and management bonuses like a normal business, Fannie lobbied Congress to a) increase the size of the mortgages they could offer b) reduce the amount of down payment required and c) reduce credit standards generally. This helped them take more and more of the mortgage market away from banks who had to make a profit without government guarantees. Like normal corporations, Fannie made lavish campaign contributions to politicians who voted as corporate executives would prefer, but being taxpayer-created the managers in effect used your money to do so.

The process of destroying the home mortgage market really got rolling during the Carter administration. Activists claimed that banks were ignoring credit-worthy blacks because of racism - which may actually have been true in some cases - but instead of investigating specific wrongs, the government simply issued a blanket requirement to banks to offer loans in market segments they'd been ignoring.

The New York Times warned of a coming disaster when credit requirements were further loosened during the Clinton administration but nobody cared. The crash came in 2008, precisely 40 years after Fannie was given stockholders.

Politicians don't care about potential downsides to whatever they do as long as there's a political upside today. We don't know how many people who benefited from Fannie's unwise loans actually voted for Rep. Frank or Sen. Dodd, but we do know that Fannie gave them a lot of money in campaign contributions.

Politicians don't care about the long term because they figure that the crash will come after they're retired or out of office and will be someone else's problem. The regulatory agencies, which are their political creations, have the same philosophy. Even if the crash comes during a particular bureaucrat's watch, nobody will be fired no matter how badly the agency performed; they're more likely to see a budget increase than to get fired.

In the case of the current crash, the politicians were fortunate that the mainstream media were in such hatred of Mr. Bush and so enamored with Mr. Obama that they didn't do their homework and show that Democrats were responsible for much of the disaster - that would have made Democrats like Mr. Obama look bad. Documenting the reasons for the crash was left to overseas media such as the Independent.

Foxes and Hen Houses

When a bank fails, the FDIC is supposed to take it over, wipe out the stockholders, and run the bank until it can be sold. The IndyMac experience shows that putting government regulators in charge of running a private business creates an appalling moral hazard and leads to far worse behavior than any normal private business would contemplate.

As the previous article spelled out, when IndyMac bank failed and the FDIC took it over and ran it as IndyMac Federal Bank, the new bank under the direct control of the government entered into wholesale foreclosure fraud, forging document en masse to boot people out of their homes lickety-split. Other private banks shrugged and followed the example of their regulators.

If a private business commits fraud, there's a chance, albeit small, that someone will blow the whistle and an executive will go to jail. If a government agency is running a business and the bureaucrats believe that committing fraud will make it easier to sell the business off and make themselves look good, they will almost certainly go ahead and commit the fraud because "if the government does it, that means it is not illegal" most of the time. Breaking the rules is pure bureaucratic reward with no risk because an attorney general who's appointed by the President is generally reluctant to institute prosecutions that will make the administration look bad.

It's a defensible idea to have an outside, independent agency looking in on business behaviors to make sure they're kosher. For this to work, alas, true independence is required.

Unfortunately, with human beings independence is almost impossible. We all know of regulators who have gone to work for the companies they previously regulated, for lavish salaries; God only knows what private arrangements were made beforehand. Not only did Rep. Barney Frank accept massive campaign contributions from Fannie and Freddie which he was supposed to be regulating, he also accepted favors of a more personal sort from a high Fannie executive.

The only way to prevent this sort of thing is to put people in charge who place honesty above their own personal gain; alas, America has a hideously bad track record of such selections in recent years. If the regulators are going to be even more corrupt than private businesses, and hide behind the power of governmental authority to boot, we're better off not having regulators at all; at least that way we know where we are. It'll be caveat emptor as it has always been whenever the rubber really meets the road.

Market Meddling is a Mess

Forcing businesses to deal with customers they do not want creates serious problems because it fouls up the normal working of the market's invisible hand.

Fannie Mae's conversion into a profit-seeking business was justified by the claim that racist bankers were ignoring thousands of credit-worthy black people. Those of us who believed in the market argued that if poor people truly could pay off loans, sooner or later somebody would lend them money and make a fortune. We've seen bankers make money on microloans to extremely poor women in India and cell phone companies make money providing banking services in Kenya and Somalia, for example. There was no reason that market forces wouldn't supply financial services to poor blacks if they were indeed worthwhile credit risks.

Unity Bank and Trust was started in Boston in 1968 to make a business of lending to lower income people whom activists said were being ignored. The bank failed.

Its successor, the Boston Bank of Commerce, was organized in 1982 to pursue the same "market." Instead of trying to operate independently, this bank partnered with larger banks and with a number of government agencies. It had a negative net worth by the mid 1990's.

After acquiring other black-owned banks in other states, the bank renamed itself OneUnited Bank in 2002. In 2010, OneUnited was the center of a House ethics investigation involving Rep. Maxine Waters who set up meetings with federal officials. She wanted them to assist the bank which was still losing money. The fact that her family had a financial interest in the institution put her in violation of the ethics rules of the US House and possibly violated the law.

The fact that this succession of well-meaning banks lost money consistently over 30 years of trying to lend to poor people despite star-studded boards of directors and federal help while nobody else wanted to make home loans to inner-city laborers might, just possibly, mean that they weren't good lending risks. The government forced regular banks to make these loans anyway and used your tax dollars to make it possible.

Result? The mortgage bubble and collapse which impoverished the already poor and also a whole lot of other people. The politicians and regulators who made it all possible have escaped unscathed, but hopefully, they will suffer in the next election.

When government messes with market forces, the market eventually pushes back with a vengeance and the worse the meddling, the harder the pushback. It's not nice to mess with Mother Nature, and despite the best efforts of socialists, the invisible hand of the market is a force of nature - human nature.

Points to Ponder

We've seen some specific lessons to be learned from the mortgage fiasco which will be very useful for those of our readership who are now, or may in the future become, Congressmen. As interesting and enlightening as these are, they're not much practical help to most us down here on the ground.

There are, however, several more general principles illustrated by the mess which are of practical value to every voter:

- Government is inherently incapable of creating value, it can only destroy value. Sometimes this is very useful - the whole point of the military is to destroy enemy countries' value - and occasionally it's a price worth paying for other reasons, but most of the time expecting the government to solve a problem is a money-wasting fool's errand.

- Government destroys any market it touches - general aviation, nuclear power, post office, home mortgages, and now student loans and health care. Government can and should enforce honest and orderly dealings, e.g. contract law and antifraud regulations, but any meddling much more detailed than that will likely create worse problems than whatever they were intended to solve.

- Regulators focus on pleasing congressmen and senators instead of on doing the jobs they're supposed to do.

It's all very well to consider how we got in this mess and take note of the lessons learned, but we still have to live in this world; we're left with the issue of what to do about the foreclosure fiasco.

It's clear that many big banks acted very badly towards the courts when filing false papers. Massive cheating on foreclosures is not acceptable even when the home owner shouldn't have been granted the mortgage in the first place.

Government is no solution because banks which were being run by the government did this a much as any bank if not more so.

So, what do we do now? The last article in this series gives our solution to the problem of regulating banks, and of regulating any business for that matter.