Close window | View original article

Harvesting Prison Labor

And other virtual feats of economic daring.

Forbes, among others, reports that Chinese prison guards force inmates to play online computer games for the guards' personal profit.

The Guardian reports that Chinese prison guards forced their inmates to work as “gold farmers,” playing games like World of Warcraft to attain virtual items which would then be sold on secondary markets.

The Guardian explained in detail how the scheme worked:

As a prisoner at the Jixi labour camp, Liu Dali would slog through tough days breaking rocks and digging trenches in the open cast coalmines of north-east China. By night, he would slay demons, battle goblins and cast spells.

Liu says he was one of scores of prisoners forced to play online games to build up credits that prison guards would then trade for real money.

It's no surprise that ambitious online social climbers who desire to gain status in virtual gaming worlds might want to reduce the effort needed to earn land, castles, or powerful weapons. Some time back, a gamer friend told us it took roughly 2,000 hours of gaming - approximately one work-year - to earn a decent sword, then win some battles, and eventually become a high-status landowner in games such as EverQuest or World of Warcraft.

Millions of gamers around the world are prepared to pay real money for such online credits, which they can use to progress in the online games.

Given that so many gamers want to avoid so much of the work, an elaborate secondary market has developed for artifacts "earned" in virtual gaming worlds. If the appropriate financial arrangements are made outside the game, two characters can meet at an agreed spot and transfer the goods.

This practice is called "gold farming." It's hard to determine exactly how much real cash is exchanged for virtual goods, but the Guardian estimates that there are 100,000 full-time gold farmers in China and that over a billion dollars worth of virtual goods were exchanged for real cash in 2008.

Spinning Virtual Straw into Real Gold

The first time we ran across gaming for profit, we read about an entrepreneur who'd set up a gaming facility in Mexico. He paid Mexicans to play games and sold their output. This didn't work for very long - his employees figured out that they could set up their own gaming accounts and go into business for themselves. It was hard to keep employees slogging away on his behalf.

Labor turnover isn't a problem in Chinese prisons. Forbes estimated that 80% of all such production of virtual goods occurs in China due to rock-bottom labor costs - prisoners don't cost the guards anything.

They can't use the prisoners full-time, though. Inmates have to do whatever manual labor the government requires before they're allowed to "play." One convict who'd left the prison when his sentence was up told the Guardian about his work schedule:

As well as backbreaking mining toil, he carved chopsticks and toothpicks out of planks of wood until his hands were raw and assembled car seat covers that the prison exported to South Korea and Japan. He was also made to memorise communist literature to pay off his debt to society.

The guards had to satisfy government work quotas before they could force the inmates to play games in their "spare" time.

"Spare" time or no, this isn't pin money. The ex-con told the Guardian that he'd heard guards bragging that they were getting 5,000-6000 Chinese yuan per day. That's between $750 and $900, not bad for a business which has no labor costs at all and very low staff turnover.

|

| What's wrong with paying your debt to society? |

Opportunity Knocks in Strange Ways

The concept of having prisoners work to help pay the costs of their imprisonment isn't new; prison labor has been sold commercially as long as there have been prisons. It's rare in the United States, though, because labor unions have lobbied for laws which restrict the commercial use of convict labor. The unions seem to be afraid that the convicts will work for lower wages than their members.

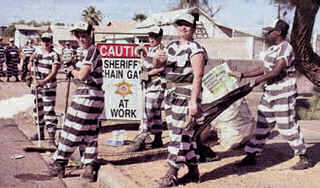

Nonetheless, there are call centers in American prisons. So long as the call center doesn't process credit card data, at 92 cents per hour, a prison-based staff is a viable alternative to offshoring. Convicts traditionally manufacture license plates, and states such as Alabama and Arizona use chain gangs to pick up roadside litter and clean graffiti off buildings despite protests from the unions and from various Chambers of Commerce.

American penologists are skeptical of computers in prisons - that's one of the major obstacles to setting up more prison-based call centers. If this issue could be addressed by locking down computers as securely as the Chinese have done, it's possible that yet another industry could bloom as long as the economics support paying the inmates a buck an hour to play games.

Welfare to Work

One of the reasons that welfare recipients have such a hard time making it into the world of work is that their skills don't make them worth minimum wage. Playing some computer games is free, however, and someone aspiring to make money gold farming might enjoy the learning curve. Would the Obama administration count gold farming as job creation?

Unlike the drug trade which delivers a real but harmful product, this industry depends on customers who swap real cash for products that don't really have any tangible existence.

Whither Virtual Goods?

Given that there's a billion-dollar market for virtual goods and that gaming itself is a multi-billion dollar industry, what next?

- Game vendors want in on the real action. So far, most of the major games haven't restricted the trade too much because having real prices quoted for virtual goods makes their games seem more desirable.

- Facebook has defined its own virtual currency, Facebook Credits, which games which exchange money are required to use.

- Second Life lets participants buy and sell on its own web site. Having figured out how to charge subscription fees for virtual action, other games will figure out how to get a piece of the real action over time.

- The World Bank reports that gold farming can have a significant impact in undeveloped countries. Entry costs are low and most of the revenue stays in the country where it's earned.

- Gaming environments can create electronic goods at will just as governments print money whenever they want. Inflation is a real possibility especially if a game starts selling goods it creates out of thin air.

- A billion bucks per year is big enough to be visible; government regulation is coming. In 2009, the Chinese government made it illegal to trade virtual goods without a license.

- Virtual economies have scams and frauds like real economies. A Second Life virtual bank named Ginko, which means "bank" in Japanese, offered 40% interest, far better than Bernie Madoff's 10%. When the bank went bust, the equivalent of $750,000 real dollars disappeared.

The usual suspects are calling for regulation of invisible economies in virtual worlds with no physical reality whatsoever, populated entirely by residents who are there of their own choice and who can withdraw at any time. Perhaps they're hoping that virtual rules for virtual economies will work better than the real ones have in the real world?

Even Dr. Seuss's Once-ler, for all his insight into the mind of the American consumer, might have found virtual goods a bit far-out - much less a virtual Lorax to complain about his online business practices. No doubt the Once-ler would have been first in line to peddle nonexistent wares as the market developed, however.

I laughed at the Lorax, "You poor stupid guy! You never can tell what some people will buy."

- Dr. Seuss