Close window | View original article

Innovate or Starve

Discourage engineering, and modern society must collapse.

On Sept 7, 2008, the New York Times electronic version published "Georgia on my Mind," the blurb for which said, "Barack Obama and John McCain need to focus, not on war, but on strengthening our capacity for innovation -- our most important competitive advantage."

The article started out criticizing the Bush administration for promising $1 billion to repair damage done to the Republic of Georgia by the recent Russian attack, then segued to commentary on the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions:

What I found missing in both conventions was a sense of priorities. Both Barack Obama and John McCain offered a list of good things they plan to do as president, but, since you can't do everything, where's the focus going to be? [emphasis added]

Wow. That's the first time we can remember a major liberal publication pointing out that we can't possibly afford to implement every idea which any politician, academic, or blogger happens to propose. Even Hillary Clinton understands this; during the recent primary, she accurately said:

I have a million ideas. The country can't afford them all.

Noticing that government has to set priorities ranks right up there with noticing that the sky is blue some of the time, but the necessity of setting priorities seems to rate as major news to Times readers.

The Times then focused on what both Hillary and we at Scragged agree should be an extremely high priority:

That focus needs to be on strengthening our capacity for innovation - our most important competitive advantage. If we can't remain the most innovative country in the world, we are not going to have $1 billion to toss at either the country Georgia or the state of Georgia.

Again, the writer says we can't afford to spend $1 billion fixing up even our own State of Georgia. We wonder what the Times thinks of our taxpayers spending many billions not fixing New Orleans?

While we still have enormous innovative energy bubbling up from the American people, it is not being supported and nurtured as needed in today's supercompetitive world. Right now, we feel like a country in a very slow decline - in infrastructure, basic research and education - just slow enough to lull us into thinking that we have all the time and money to play around in Tbilisi, Georgia, more than Atlanta, Georgia. [emphasis added]

As Chuck Vest, the former president of M.I.T., said to me: "Both candidates have spoken a lot about 'change,' but in most areas of need, innovation is the only mechanism that can actually change things in substantive ways. Innovation is where creative thinking and practical know-how meet to do new things in new ways, and old things in new ways.

Dr. Vest is right on. Every increase in our standard of living from the time of muscle-powered farming where most people never traveled further than 10 miles from their place of birth and most people died in their 30's is due entirely to technological innovation.

The most important aspect of technical innovation has always been finding new energy sources to make it possible for people to use more and more energy to enrich their lives. If you have an automobile available, your life can be richer than if you have to walk everywhere, for example, but a person who drives a car consumes a lot more energy than someone who walks everywhere.

"The irony of ignoring innovation as a theme for our times is that the U.S. is still the most innovative nation on the planet," Vest added. "But we can only maintain that lead if we invest in the people, the research that enable it and produce a policy environment in which it can thrive rather than being squelched. Our strong science and technology base built by past investments, our free market economy built on a base of democracy and a diverse population are unmatched to date; but we are taking it for granted."

Unfortunately, most of what any new administration would have to do to encourage innovation consists of finding all the stupid things our government is doing which retard innovation and making the bureaucracy stop holding us back. We've discussed a number of really dumb things we do:

- Deny bright foreigners student visas so that our colleges set up branches overseas to avoid losing customers. This ensures that when these students start businesses, the new businesses won't be in the United States and all the economic gains will go to some other society.

- Worry about gender balance in our research labs. Instead of focusing on who can achieve innovative breakthroughs, the NSF is worrying about gender and racial balance of the researchers.

- The "peer review" system for allocation research money assures that nothing truly innovative will ever get a grant. Geniuses, by definition, have no peers. Peer review would never have funded Einstein, for example. Neils Bohr, the Nobel-prize winner who dominated physics as Einstein was getting started thought Einstein was crazy.

The peer review system is even more broken than we realized when we first wrote it up. The article "Strategies for Nurturing Science's Next Generation" from Science News of June 20, 2008 has the usual complaints about not enough funding which we've learned to expect from all interest groups who feed at the public trough, but Science News also lists substantive issues with respect to innovation:

First is the difficulty assistant professors face in obtaining stable funding for their research. The nation invests 25 to 30 years in the education of these faculty, who then compete with perhaps a hundred other applicants to land a position; finally, when they should be in their laboratories making discoveries and in classrooms training the next generation, they are driven to their offices to become serial grant-writers. And their students and postdoctoral fellows, listening a bit too seriously to their mentors' travails, start pondering alternative careers.

Few creative geniuses are able to write convincing proposals; our system rewards whomever writes the best speculative fiction. Having made this point, the article gets to the heart of the matter:

The second issue: As research funds get tighter, review panels shy away from high-risk, high-reward research, and investigators adapt by proposing work that's safely in the "can-do" category. The clear danger is that potentially transformative research - that which has a chance to disrupt current complacency, connect disciplines in new ways or change the entire direction of a field, but at the same time incurs the very real possibility of failure - finds scant support. [emphasis added]

Academics don't appreciate having their careers disrupted by "transformative research" any more than businesses appreciate being disrupted by new competitors; they don't want anything funded that would question whatever papers qualified them for tenure.

As we explained in an earlier article, anything in the "can do" category is not research. Dictionary.com says: research - Diligent and systematic inquiry or investigation into a subject in order to discover or revise facts, theories, applications,etc.

When you're really looking for new facts, you never know what you'll find or whether you'll find anything at all; your proposal can't say what you'll find because you haven't found it yet. "Can do" projects are not research; funding agencies commit fraud when they tell us they're funding "research."

Given the difficulty of changing entrenched bureaucratic habits, the next president probably can't fix the existing agencies which fund "can do" projects instead of research. Sen. McCain's proposal of offering prizes for solving problems has worked in the past. The more money we take away from agencies to offer prizes, the more innovation we'll get.

Innovation is Vital to Survival

The Times is completely correct in that the next administration ought to address innovation, but the Times described innovation as a matter of lifestyle. They give the impression that innovation is important because innovation makes it possible for us to live better than people in other countries.

That's certainly true, but the real issue, which the Times missed, is that we need innovation to continue living at all. Innovation is not merely required to sustain our life style, it's required to sustain life itself.

Here's why.

In 2007, the EPA said there were over 285,000,000 people in the United States. About 960,000 are farmers. Less than a million people grow enough food for 285 million.

In 1935, the number of farms in the United States peaked at 6.8 million as the population edged over 127 million, less than half of what our population is now. Increased demand for food has been met with large, productive pieces of farm equipment, improved crop varieties, commercial fertilizers, and pesticides.

There were 27.5 acres per farm worker in 1890 and 740 acres per worker in 1990. Americans grow so much food that lots of people eat too much and we have to pay farmers not to grow as much as they could.

One American farmer now feeds 285 people. How do we do this? With large pieces of farm equipment, much fertilizer, and pesticides.

What makes farm equipment go? Gasoline. Fertilizer is made from petroleum, as are pesticides.

In 1935, there were a few tractors, but nothing like we have now. In 1935, farmers fed fewer than half as many people as we have now using muscle-powered farming, horse and buggy agriculture.

If we stop using petroleum as we do now, if we ever go back to muscle-powered farming, we'll be able to feed maybe half our present population. Without gasoline-powered farming, half our people will starve to death.

Gasoline-powered farming requires well-educated farmers to build, run, and maintain machines. It needs well-educated workers to make the machines; the skills needed to machine replacement parts can't be learned overnight. High-tech farming needs well-educated workers to run refineries to make the gasoline, to make fertilizer, and trucks that ship fertilizer to the fields and ship food back.

Our students aren't learning what they need to know to manage this; we could lose our ability to operate our industrial farming system.

Eduction isn't the only problem. We all know that world demand for energy has increased as Chinese and Indians have become wealthy enough to afford cars, refrigerators, and air conditioners. Food prices are going up as our government commands that we turn 15% of our corn crop into 2% of our automobile fuel.

If we expect to continue to farm as in the past, if we expect not to starve to death, we need to find new energy sources soon. Not starving won't be much fun if the energy needed to raise food costs so much that eating takes all our disposable income.

Innovation isn't just a matter of life style, it's a matter of life and death.

Innovation Needs More Than Science

The Times quotes Dr. Vest as saying, "... we can only maintain that lead [in innovation] if we invest in the people, the research that enable it and produce a policy environment in which it can thrive rather than being squelched." The federal government is getting worse and worse at funding breakthrough science that enables innovation, but they're also squelching the implementation of innovative ideas after the science is done.

Consider nuclear power. The basic idea came from one man, Albert Einstein. He persuaded some people to collect data to test his theory as part of an experiment they were doing anyway.

The extra data, which came at very low cost, vindicated Einstein and forced Neils Bohr to admit that Einstein wasn't crazy after all. This demonstrates that the only difference between a genius and a crackpot is that the genius turns out to be right; nobody can tell up front, not even another genius.

Once people accepted Einstein's formula that E=MC2, the problem was figuring how to get actual energy out of his formula. The Manhattan Project which led to the first atomic bomb required the services of the nation's top physicists, but it needed far more engineers to build equipment, carry out experiments, and fabricate the first bomb. After the war, converting the technology from a bomb to a reactor that could power naval vessels and generate electricity required hordes and hordes of engineers; very few scientists were needed once the basic research was out of the way.

In addition to squelching innovative researchers through the dead hand of peer review as pointed out in the Science News article quoted above, current federal policy is drying up the supply of new engineers. When I was in college, the department of nuclear engineering was full of busy-brights who looked forward to careers providing low-cost, safe electricity through nuclear energy. When the political climate turned against nuclear energy, the department shriveled and nearly died. Engineers don't go where they aren't wanted.

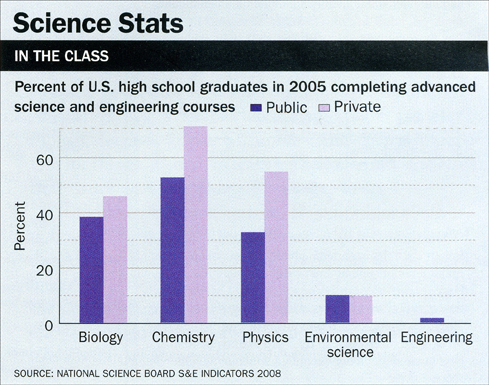

This figure shows that hardly any high school graduates are going into engineering. Potential engineers have noted that society doesn't want new highways or bridges; construction projects are tied up in environmental battles for years at a time. Society doesn't want new refineries or electric generating plants, we built our last oil refinery 30 years ago. Why should any intelligent person go into engineering when society has showed engineers the back of its hand?

Without engineers, we won't be able to build new wind farms. Without manufacturing engineers to build new auto plants, we won't be able to build new green automobiles. Without design engineers, we won't be able to build new solar energy collection systems.

Without engineers, we won't be able to implement any of the fine new alternate energy systems our politicians are demanding even if the scientists figure out how to make them work.

The doomsayers at the Times may be right - we may lose our lifestyle after all, and with it, many of our lives.