Close window | View original article

The End of Our Space Age

Outer space doesn't make any money, so we're abandoning it.

In "The end of the Space Age," the Economist offers a pretty bleak assessment of the chances of further progress in space; as the subtitle has it, "Inner space is useful. Outer space is history."

By "inner space," they mean the 36,000 kilometers out to "synchronous orbit" where a satellite takes 24 hours to orbit the earth and therefore stays over the same place all the time.

And viewed this way, the Space Age has been a roaring success. Telecommunications, weather forecasting, agriculture, forestry and even the search for minerals have all been revolutionised. So has warfare. No power can any longer mobilise its armed forces in secret. The exact location of every building on the planet can be known. And satellite-based global-positioning systems will guide a smart bomb to that location on demand.

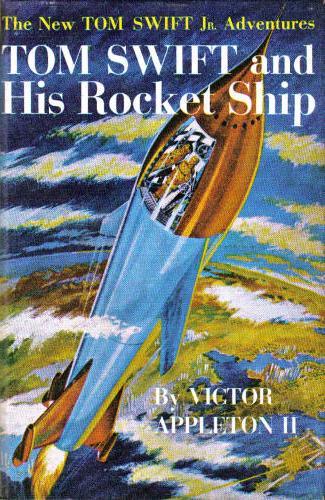

The usefulness of satellites was not at all what the early space explorers had in mind. In the visions of the great early rocket scientists and adventurers, the planets if not the stars beckoned and were there for the taking. The early rocketeers truly wanted to "Boldly go where no man has gone before," and what's more, had every expectation that they or, at worst, their kids actually would.

Your humble correspondent fondly recalls tickets being offered for sale in the mid-1960s, with all seriousness, for the "First commercial flight to the moon." Only his penurious status as a college student at the time kept him from shelling out for one. Half a century on, such an advertisement would be such a transparent joke that it wouldn't even be worth a fraud investigation.

|

|

| What went wrong? |

|---|

The Economist observes that the original dream has died:

No longer. It is quite conceivable that 36,000km will prove the limit of human ambition. It is equally conceivable that the fantasy-made-reality of human space flight will return to fantasy. It is likely that the Space Age is over. ...

Outside it [the 36,000 km orbit], though, the vacuum will remain empty. There may be occasional forays, just as men sometimes leave their huddled research bases in Antarctica to scuttle briefly across the ice cap before returning, for warmth, food and company, to base. But humanity’s dreams of a future beyond that final frontier have, largely, faded.

They base this belief on the end of NASA's Space Shuttle program - the last flight was on July 8, 2011.

It may seem bizarre to think of now, but the shuttle was originally advertised and designed as a low-cost vehicle for getting into orbit for an affordable fee. Its official name, "Space Transportation System," reminds us of the original objective. Since getting into orbit is the most expensive part of exploring space, cutting the cost would have been a good foundation for further progress.

Another Spectacular Government Failure

The shuttle program failed miserably and spectacularly in every possible way. Instead of working more or less like an airline with relatively brief turnaround times before returning to the skies, the handful of Shuttles made far fewer flights than promised at such ludicrously greater cost that there was simply no way to keep the program going.

As we've explained, part of the problem lies in the difference between a "project," as in "the Apollo project," and a "process."

A project is something you do once. It's OK to have many steps in a project cost more than they might because you aren't going to do it often enough to make it worth making the investment needed to reduce the cost.

A "process," in contrast, happens over and over. You have to engage in continuous "process engineering" to cut costs over time.

NASA never made the switch from the project thinking they used to get to the Moon to the process thinking they should have used for the Shuttle. Just like Apollo, Shuttles needed vast herds of expensive ground-based support people who had little to do between launches. Their failure to re-engineer the process doomed the Shuttle.

The Problem With All Government Activity

The Shuttles flew from 1981 until 2011. The ongoing outlandish costs of NASA's Space Transportation "Service" over that 30-year period illustrates the problem with government providing any service - there's no economic pressure to cut costs. With government being the only customer and government paying all the bills, no one really cares about the price.

The Shuttle never had private-sector competition or customers. "Inner space," that is, putting satellites into earth orbit, has both competition and private customers. As one would expect, "inner space" costs are being reduced over time by market forces because there's economic value to be gained there. There is no private sector activity in outer space because there isn't any value out there, at least not yet.

Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain funded Columbus' trip of exploration to the Indies, but this was not for the simple sake of acquiring knowledge. Both they and he were frankly interested in gaining wealth. They were venture capitalists who happened on a big hit.

Neither the King, Queen, nor Columbus had no idea that the New World even existed because Columbus' estimate of the earth's circumference was off by 5,000 miles or so. They were looking for a short cut to China and the Spice Islands where they knew there was wealth to be had; a shorter, faster means of shipping it home would obviously more than repay the investment.

Finding the New World which offered literally tons of gold with no one to dispute their claim save for a few Indians who were wiped out by smallpox was a fortunate accident, much like being an early investor in Google, Microsoft or Apple was for a fortunate few. It's conceivable that there's something in outer space that's worth the trouble of getting there, as science fiction writers have imagined for decades now.

In the real world, though, nobody has any idea as to what that might be, much less where to find it or how to get it. No likely return equals no private investment, which also equals no pressure to lower costs.

Ego or Money?

When President Kennedy decided to spend billions getting to the moon, nobody could see any remotely plausible path to wealth from adventure in space. JFK was well aware of this and didn't even try to sell the space program as a profitable venture; he'd have been laughed at. Instead, he sold it as a grand adventure and as a way to compete with the Soviets, both of which it unarguably was.

As it turned out, the technologies which were developed from the research NASA needed to get to the moon gave America a huge economic boost. Government taxed all this economic activity, of course, and got its Apollo money back and then some.

Once the public found out how much we benefited from research, the National Science Foundation was funded to continue the flow of new technology. Unfortunately, the funding process has been overtaken by politics - grants are made based on political connections and political correctness. The results have been increasingly meager in terms of generating taxable economic activity.

If President Obama were serious about creating new jobs as well as knocking us out of our national malaise, he might consider setting a goal of getting to Mars or of setting up a manned base on the moon. Our experience with NASA shows that research funded in order to reach a specific, well-understood goal gives unpredictable but very valuable side benefits. Our later experience with NSF shows that research funded merely for its own sake doesn't get anywhere worth going, at least not in a visible time frame.

The Economist points out that the Chinese have a space program and are talking about returning to the moon, but isn't confident that they'll continue:

The chances are that the Chinese government, like Richard Nixon’s in 1972, will say “job done” and pull the plug on the whole shebang.

This could happen, but the Chinese might be smarter than President Nixon. They certainly have the advantage of knowing how badly NSF research funding turned out once the goal-directed focus of the Apollo program ended.

Modern Chinese research programs are tightly focused on electric cars, disease treatment, and other matters of commercial import. They're certainly aware of the national ego boost which landing on the moon would give and they spent vast sums boosting their national ego at the Olympics.

Who knows? They might also understand the economic value of doing the research needed to explore space. If they do, mankind will advance, but the stars will no longer be ours.

There may well be gold of some sort in them thar asteroids, but it won't be Americans bringing it home.