Teens Lost in Virtual Space

Are we raising a generation of social misfits?

-

Tools:

Our twentieth century progenitors lived at a time when the running speed of a horse was considered blazingly fast; as times have changed our concept of speed has too. And even the SR 71 reconnaissance aircraft of the late 20th century at over Mach 3 cannot approach the speed of change that has become usual in today’s world.

Blindingly fast computers are now the norm. Quantum computing is in the offing, and that will present our society with imponderable difficulties in the future. We don’t seem to be handling all the problems that we have now very effectively, to end this mixed metaphor.

Our children in the schizophrenic here-and-now are presented with challenges that never existed before. This author’s wife’s granddaughter, Mary (not her real name), who is 14 and in the eighth grade, is facing a world that she is totally unprepared for, as most of her peers also are not.

Mary is not doing it well. Her mother is normally intelligent and fairly well-adjusted, but she, like the rest of us, did not foresee the change that came about in her daughter. Schools are not equipped to deal with her; there is an entirely new set of behaviors that she and kids of her age are exhibiting. Smartphones and electronic self-entertainment are making socialization into an uphill slog for her.

Her attitude is an amazing amalgam of schizophrenia, indignation at having ever been born, and smartassyishness (to coin a word). This writer remembers being that age, and possessing a modicum of all those traits, but Mary displays them in spades.

Mary is non-communicative, which is common among kids that age; that has become the prepubescent/pubescent norm. She acts as if she thinks that adults are idiots and that we cannot possibly understand her; again, common.

Where it seems that she takes a departure from normal teenage rebellion is in the way she is coping with her frustrations – she simply isn’t. She spends whole days in her room with the door tightly closed, giving surly responses to any attempt at communication through the 1 3/8” of hollow core door that provides isolation from the world around her.

It was with the best of intentions that her grandmother and this writer presented her with a new iPhone last year. We had decided that her sister, two years her junior, was in need of a means of communication with her mother in case of emergencies. If you buy a phone for one girl, then you must provide a similar phone for the sister. That’s a law of some kind.

Upon receiving that new iPhone, her first official act was to run up a monthly bill quintuple her baseline charge. She found out about iTunes very quickly, and we had not provided the necessary restrictions on purchases. Her punishments after the first month were not enough to affect behavior modification; further restrictions and finally the removal of the phone from her custody for a period of time was necessary.

The punishments that Mary brought upon herself were regarded as an intrusion – a series of unfair procedures forced upon her by her parents. She could almost be heard mumbling her mantra, “it’s not my fault.” This is the liberal excuse for everything that her classroom training has taught her.

She is incapable of facing the world some days, and on others offers up a surliness of demeanor that makes those having to deal with her – all of them – give up with a shrug. She is fortunate that no one has rained down upon her head the physical blows that might be appropriate.

Kids her age are difficult, and have been since time immemorial, but Mary typifies a new generation that is unpleasant, uncaring, and unwilling to communicate. She exists in her own little miserable world, kept company by her ubiquitous iPhone (when she’s allowed to have it.)

It is that iPhone that is at the heart of the problem, and there are many of us that have learned this unforeseen consequence of technology. It is difficult enough for adults to deal with, but for young folks who have known nothing else, it has developed its own set of systemic problems. The problems of adolescents are not new, but the severity and ubiquity of them is.

Utilizing private communication within her set of “friends” and using available apps (her mother keeps tight control over which apps she may have) she has developed an isolation cell in which she lives. She refuses offers of help with her studies, keeping the assignments and expectations tightly to herself. Her grades are awful, and she is in danger of being held back – the proper word is failing – this year, early as it is.

We can see plainly that this trend in technology has failed many kids miserably. Their age group has a few students who are exceeding expectations and setting a torrid pace of intellectual accomplishment, but a large number of her group are failing at the daunting task of keeping up with the pace-setting few.

It is more than not learning lessons in school. The bigger problem comes about with not coping with human relationships and social inter-activity. In many respects, these kids are closed off from the exploration they deserve to do.

Society-wide, there has been a complete change in the social expectations of many people over the past seven or eight years. “Friends”’ are now individuals with whom face-to-face contact may have never occurred. It’s an amazing downgrading of relationship status to something very casual and disposable, which makes this writer wonder if there are real friends anymore within the teen years.

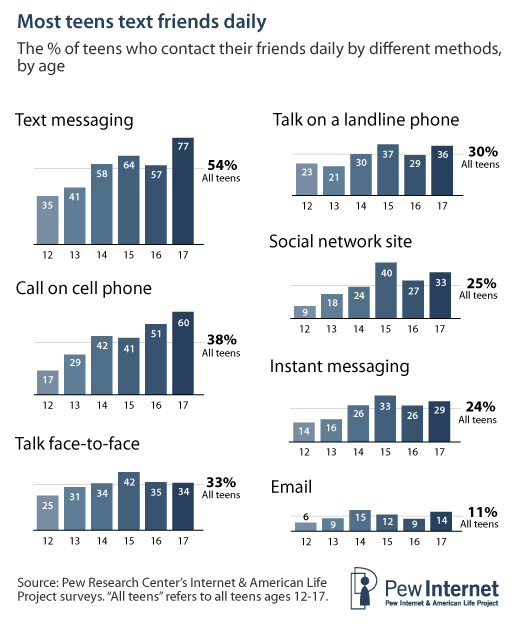

The statistics of the world of teens and their use of technology are daunting:

More interesting facts about texting:

Two-thirds of teens say they will text their friends rather than talk to them.

One third send more than 100 texts per day (3000 per month.)

One half send 50 or more per day; boys: 30 per day; girls: 80 per day. This ratio is typical of all means of communication. Girls are definitely more cell phone users than boys are.

Typical teen: 20 texts per day.

Voice calls, especially for conversing with parents and other adults is still the preferred method, but only by a little bit.

Other uses for cell phones:

- 83% cameras.

- 60% play music

- 46% play games

On line videos, instant message, social networking, email, purchases, and general-purpose use make up the balance of time teens spend on their phones.

Too much time is spent looking at a 3-inch screen to the exclusion of real life; this prevents them from being able to progress in the way that humanity always has. In the eyes of this writer, this is the biggest part of the problem.

The kids in their mid teens are the first wave. We can expect this to continue as we ignore the lessons of the past.

Ever since the advent of radio and TV, it has been overwhelmingly tempting for stressed parents to allow electronic babysitting to become an easy way of dealing with the problems of children. Today’s more powerful apps keep them occupied so that they don’t bother adults even more than the TV shows of yesterday. They provide us with a lot of mindless drivel, some of it posing as social interaction, but most of that is merely activity with no intellect.

The young people willingly participate, and interact with one another, pretending that they have friends. But these relationships are not well-rounded ones – many of them lack the intellectual vigor of a face-to-face interchange of ideas.

Our modern challenge is to figure out a way to keep our kids from being limited by the temptations offered by electronic artifice; an article in the Atlantic addressed smart phones and the next generation.

There is a modicum of encouraging news coming from the school where my wife is the chief administrator: their school curriculum coordinator has at least acknowledged the seriousness of this problem, has begun recently to address it, and will soon attempt to provide adjustments to the curriculum. Many schools are attacking this problem, and there will probably be solutions found eventually.

With luck, these changes will be made in time to keep more of these kids from experiencing the withdrawal from reality that Mary has had to cope with. But she, and her whole generation, may suffer for a very long time from the intrusions of the new socialization that she is experiencing.

-

Tools:

What does Chinese history have to teach America that Mr. Trump's cabinet doesn't know?

I sure miss the old days when we sat by the corral and watched the barn animals copulate.

Let's not forget that when we were kids in school, we would pass notes to each other. Texting is today's (supercharged) equivalent.

And look on the bright side. All of the kids today know how to type.

There does seem to be a fair amount of one-up-manship on social media among teens. " I don't feel great..", " I'm tired out from practice..." " oh yeah, I feel suicidal..". Teens often don't have very good filters and they are not very good long term planners. Emotion and spur of the moment reign supreme. Unfortunately in this age of permanency on the web, dumb comments or pictures can stay around forever.

This isn't that new though. In the late 20th Century, the big decision was to let kids have a phone in their room. If you gave in, kids would rush home and continue the conversations they had all day in school, on the bus, at practice etc. Usually the excuse was " discussing homework". Fortunately, what they said wasn't recorded.

I have a very simple cell phone which I use almost entirely for communication within my own family. I send a few emails, and read a fair amount of them. I am only recently becoming aware of how much digital communication has come to dominate the lives of people younger than myself, and of all the negative side effects which come with this behavior. I think that what the article writer describes is a serious menace,and not just a nuisance. I believe that it describes a growing portion of society that is unable to communicate effectively or to establish mature relationships. I don't believe that democratic self-government can really survive in such a situation.

Incidentally, I don't actually agree that teenagers "have always been like this"; I don't even believe that there has always been an age group that we know as "teenagers". Before the 20th Century (and in many non-industrialized societies even today)individuals transitioned directly from childhood to adulthood with occupational and family responsibilities. Maintaining a special, deferred-maturity, class of "teenagers" may be an expensive luxury that our society cannot afford for much longer.

Michael Greenberg: Sorry, that's "thumbing", not typing. It's a skill I'll never possess but one I expect I'll not need with my ancient flip-phone and what will probably follows it.

My wife used to call me her "network administrator", I'm no longer that guy and that upsets me ... but not much anymore.

"dif-tor heh smusma"